A plasma (often ionized gas, but see Pseudo-plasma), is a gaseous substance consisting of free charged particles, such as electrons, protons and other ions, that respond very strongly to electromagnetic fields. The free charges make the plasma highly electrically conductive, so that it may carry electric currents, and generate magnetic fields. This may cause the plasma to constrict (or pinch) into filaments, generate particle beams, emit a wide range of radiation (radio waves, light, microwave, x-ray, gamma and synchrotron radiation), and form cellular regions of plasma with similar characteristics (eg. magnetosphere, interplanetary medium).

Plasma is usually considered to be a distinct phase of matter from solids, liquids, and gases because of its unique properties, that it is often called the “fourth state of matter”[1], or even the “first state of matter”[2][3]

Plasma typically takes the form of neutral gas-like clouds or charged ion beams, but may also include dust and grains, called dusty plasmas.[4] They are typically formed by heating and ionizing a gas, stripping electrons away from atoms, thereby enabling the positive and negative charges to move freely.

Plasmas was first identified in a discharge tube (or Crookes tube), and so described by Sir William Crookes in 1879 (he called it “radiant matter”)[5]. The nature of the Crookes tube “cathode ray” matter was subsequently identified by British physicist Sir J.J. Thomson in 1897[6], and dubbed “plasma” by Irving Langmuir in 1928 [7], perhaps because it reminded him of a blood plasma.[8] Langmuir wrote:

- “Except near the electrodes, where there are sheaths containing very few electrons, the ionized gas contains ions and electrons in about equal numbers so that the resultant space charge is very small. We shall use the name plasma to describe this region containing balanced charges of ions and electrons.”[7]

Contents

Common plasmas

Plasmas are the most common phase of matter. Some estimates suggest that up to 99% of the entire visible universe is plasma[9]. Since the space between the stars is filled with a plasma, albeit a very sparse one (see interstellar medium and intergalactic space), essentially the entire volume of the universe is plasma (see astrophysical plasmas). In the solar system, the planet Jupiter accounts for most of the non-plasma, only about 0.1% of the mass and 10−15% of the volume within the orbit of Pluto. Notable plasma physicist Hannes Alfvén also noted that due to their electric charge, very small grains also behave as ions and form part of plasma (see dusty plasmas).

| Common forms of plasma include | ||

|

|

|

Plasma properties and parameters

Definition of a plasma

Although a plasma is loosely described as an electrically neutral medium of positive and negative particles, a more rigorous definition requires three criteria to be satisfied:

- The plasma approximation: Charged particles must be close enough together that each particle influences many nearby charged particles, rather than just the interacting with the closest particle (these collective effects are a distinguishing feature of a plasma). The plasma approximation is valid when the number of electrons within the sphere of influence (called the Debye sphere whose radius is the Debye (screening) length) of a particular particle is large. The average number of particles in the Debye sphere is given by the plasma parameter, Λ.

- Bulk interactions: The Debye screening length (defined above) is short compared to the physical size of the plasma. This criterion means that interactions in the bulk of the plasma are more important than those at its edges, where boundary effects may take place.

- Plasma frequency: The electron plasma frequency (measuring plasma oscillations of the electrons) is large compared to the electron-neutral collision frequency (measuring frequency of collisions between electrons and neutral particles). When this condition is valid, plasmas act to shield charges very rapidly (quasineutrality is another defining property of plasmas).

Ranges of plasma parameters

| Typical ranges of plasma parameters: orders of magnitude (OOM) | ||

| Characteristic | Terrestrial plasmas | Cosmic plasmas |

| Size in metres |

10−6 m (lab plasmas) to 102 m (lightning) (~8 OOM) |

10−6 m (spacecraft sheath) to 1025 m (intergalactic nebula) (~31 OOM) |

| Lifetime in seconds |

10−12 s (laser-produced plasma) to 107 s (fluorescent lights) (~19 OOM) |

101 s (solar flares) to 1017 s (intergalactic plasma) (~17 OOM) |

| Density in particles per cubic metre |

107 m-3 to 1032 m-3 (inertial confinement plasma) |

100 (i.e., 1) m-3 (intergalactic medium) to 1030 m-3 (stellar core) |

| Temperature in kelvins |

~0 K (crystalline non-neutral plasma[12]) to 108 K (magnetic fusion plasma) |

102 K (aurora) to 107 K (solar core) |

| Magnetic fields in teslas |

10−4 T (lab plasma) to 103 T (pulsed-power plasma) |

10−12 T (intergalactic medium) to 1011 T (near neutron stars) |

Degree of ionization

For plasma to exist, ionization is necessary. The degree of ionization of a plasma is the proportion of atoms which have lost (or gained) electrons, and is controlled mostly by the temperature. Even a partially ionized gas in which as little as 1% of the particles are ionized can have the characteristics of a plasma (i.e. respond to magnetic fields and be highly electrically conductive). The degree of ionization, α is defined as α = ni/(ni + na) where ni is the number density of ions and na is the number density of neutral atoms.

Temperatures

Plasma temperature is commonly measured in Kelvin or electron volts, and is (roughly speaking) a measure of the thermal kinetic energy per particle. In most cases the electrons are close enough to thermal equilibrium that their temperature is relatively well-defined, even when there is a significant deviation from a Maxwellian energy distribution function, for example due to UV radiation, energetic particles, or strong electric fields. Because of the large difference in mass, the electrons come to thermodynamic equilibrium among themselves much faster than they come into equilibrium with the ions or neutral atoms. For this reason the ion temperature may be very different from (usually lower than) the electron temperature. This is especially common in weakly ionized technological plasmas, where the ions are often near the ambient temperature.

Based on the relative temperatures of the electrons, ions and neutrals, plasmas are classified as thermal or non-thermal. Thermal plasmas have electrons and the heavy particles at the same temperature i.e. they are in thermal equilibrium with each other. Non thermal plasmas on the other hand have the ions and neutrals at a much lower temperature (normally room temperature) whereas electrons are much “hotter”.

Temperature controls the degree of plasma ionization. In particular, plasma ionization is determined by the electron temperature relative to the ionization energy (and more weakly by the density) in accordance with the Saha equation. A plasma is sometimes referred to as being hot if it is nearly fully ionized, or cold if only a small fraction (for example 1%) of the gas molecules are ionized (but other definitions of the terms hot plasma and cold plasma are common). Even in a “cold” plasma the electron temperature is still typically several thousand degrees Celsius. Plasmas utilized in plasma technology (“technological plasmas”) are usually cold in this sense.

Densities

Next to the temperature, which is of fundamental importance for the very existence of a plasma, the most important property is the density. The word “plasma density” by itself usually refers to the electron density, that is, the number of free electrons per unit volume. The ion density is related to this by the average charge state \(\langle Z\rangle\) of the ions through \(n_e=\langle Z\rangle n_i\). (See quasineutrality below.) The third important quantity is the density of neutrals \(n_0\). In a hot plasma this is small, but may still determine important physics. The degree of ionization is \(n_i/(n_0+n_i)\).

Potentials

The magnitude of the potentials and electric fields must be determined by means other than simply finding the net charge density. A common example is to assume that the electrons satisfy the Boltzmann relation:

- \(n_e \propto e^{e\Phi/k_BT_e}\).

Differentiating this relation provides a means to calculate the electric field from the density:

- \(\vec{E} = (k_BT_e/e)(\nabla n_e/n_e)\).

It is, of course, possible to produce a plasma that is not quasineutral. An electron beam, for example, has only negative charges. The density of a non-neutral plasma must generally be very low, or it must be very small, otherwise it will be dissipated by the repulsive electrostatic force.

In astrophysical plasmas, Debye screening prevents electric fields from directly affecting the plasma over large distances (ie. greater than the Debye length). But the existence of charged particles causes the plasma to generate and be affected by magnetic fields. This can and does cause extremely complex behavior, such as the generation of plasma double layers, an object that separates charge over a few tens of Debye lengths. The dynamics of plasmas interacting with external and self-generated magnetic fields are studied in the academic discipline of magnetohydrodynamics.

Magnetization

A plasma in which the magnetic field is strong enough to influence the motion of the charged particles is said to be magnetized. A common quantitative criterion is that a particle on average completes at least one gyration around the magnetic field before making a collision (ie. \(\omega_{ce}/\nu_{coll} \gt 1\) where \(\omega_{ce}\) is the “electron gyrofrequency” and \(\nu_{coll}\) is the “electron collision rate”). It is often the case that the electrons are magnetized while the ions are not. Magnetized plasmas are anisotropic, meaning that their properties in the direction parallel to the magnetic field are different from those perpendicular to it. While electric fields in plasmas are usually small due to the high conductivity, the electric field associated with a plasma moving in a magnetic field is given by E = –V x B (where E is the electric field, V is the velocity, and B is the magnetic field), and is not affected by Debye shielding.[14]

Comparison of plasma and gas phases

Plasma is often called the fourth state of matter. It is distinct from the three lower-energy phases of matter; solid, liquid, and gas, although it is closely related to the gas phase in that it also has no definite form or volume. There is still some disagreement as to whether a plasma is a distinct state of matter or simply a type of gas. Most physicists consider a plasma to be more than a gas because of a number of distinct properties including the following:

| Property | Gas | Plasma | ||

| Electrical Conductivity | Very low

|

Very high

|

||

| Independently acting species | One

|

Two or three Electrons, ions, and neutrals can be distinguished by the sign of their charge so that they behave independently in many circumstances, having different velocities or even different temperatures, leading to phenomenon such as new types of waves and instabilities |

||

| Velocity distribution |

|

May be non-Maxwellian Whereas collisional interactions always lead to a Maxwellian velocity distribution, electric fields influence the particle velocities differently. The velocity dependence of the Coulomb collision cross section can amplify these differences, resulting in phenomena like two-temperature distributions and run-away electrons. |

||

| Interactions | Binary Two-particle collisions are the rule, three-body collisions extremely rare. |

Collective Each particle interacts simultaneously with many others. These collective interactions are about ten times more important than binary collisions. |

Complex plasma phenomena

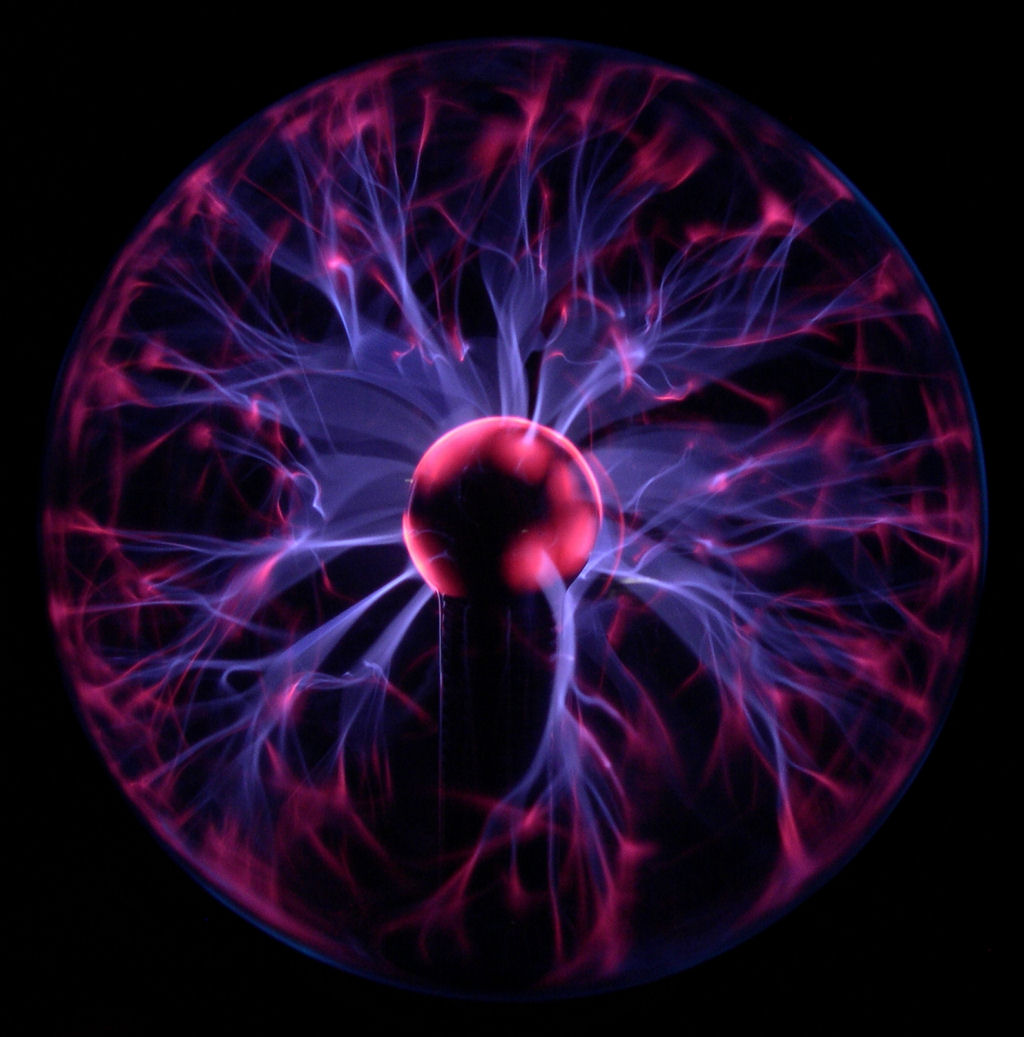

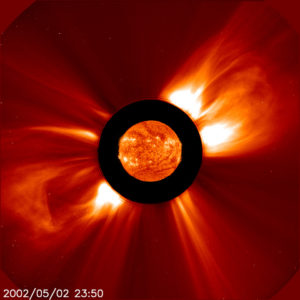

Although the underlying equations governing plasmas are relatively simple, plasma behaviour is extraordinarily varied and subtle: the emergence of unexpected behaviour from a simple model is a typical feature of a complex system. Such systems lie in some sense on the boundary between ordered and disordered behaviour, and cannot typically be described either by simple, smooth, mathematical functions, or by pure randomness. The spontaneous formation of interesting spatial features on a wide range of length scales is one manifestation of plasma complexity. The features are interesting, for example, because they are very sharp, spatially intermittent (the distance between features is much larger than the features themselves), or have a fractal form. Many of these features were first studied in the laboratory, and have subsequently been recognised throughout the universe. Examples of complexity and complex structures in plasmas include:

Filamentation

- See main article, filamentation.

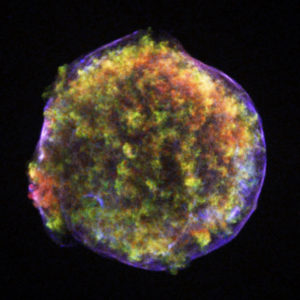

The striations or “stringy” things,[15] seen in many plasmas, like the plasma ball (image above), the aurora,[16] lightning,[17] electric arcs, solar flares[18], and supernova remnants[19] They are sometimes associated with larger current densities, and are also called magnetic ropes,[20]. (See also Plasma pinch)

Shocks or double layers

Narrow sheets with sharp gradients, such as shocks or double layers which support rapid changes in plasma properties. Double layers involve localised charge separation, which causes a large potential difference across the layer, but does not generate an electric field outside the layer. Double layers separate adjacent plasma regions with different physical characteristics, and are often found in current carrying plasmas. They accelerate both ions and electrons.

Electric fields and circuits

Quasineutrality of a plasma requires that plasma currents close on themselves in electric circuits. Such circuits follow Kirchhoff’s circuit laws, and possess a resistance and inductance. These circuits must generally be treated as a strongly coupled system, with the behaviour in each plasma region dependent on the entire circuit. It is this strong coupling between system elements, together with nonlinearity, which may lead to complex behaviour. Electrical circuits in plasmas store inductive (magnetic) energy, and should the circuit be disrupted, for example, by a plasma instability, the inductive energy will be released as plasma heating and acceleration. This is a common explanation for the heating which takes place in the solar corona. Electric currents, and in particular, magnetic-field-aligned electric currents (which are sometimes generically referred to as Birkeland currents), are also observed in the Earth’s aurora, and in plasma filaments.

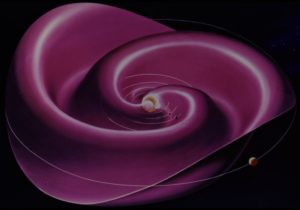

Cellular structure

Narrow sheets with sharp gradients may separate regions with different properties such as magnetization, density, and temperature, resulting in cell-like regions. Examples include the magnetosphere, heliosphere, and heliospheric current sheet. Hannes Alfvén wrote: “”From the cosmological point of view, the most important new space research discovery is probably the cellular structure of space. As has been seen, in every region of space which is accessible to in situ measurements, there are a number of `cell walls’, sheets of electric currents, which divide space into compartments with different magnetization, temperature, density, etc .”[23]

Critical ionization velocity

The Critical ionization velocity is the relative velocity between an (magnetized) ionized plasma and a neutral gas above which a runaway ionization process takes place. The critical ionization process is a quite general mechanism for the conversion of the kinetic energy of a rapidly streaming gas into ionization and plasma thermal energy. Critical phemonema in general are typical of complex systems, and may lead to sharp spatial or temporal features.

Ultracold plasma

The key point about ultracold plasmas is that by manipulating the atoms with lasers, the kinetic energy of the liberated electrons can be controlled. Using standard pulsed lasers, the electron energy can be made to correspond to a temperature of as low as 0.1 K, a limit set by the frequency bandwidth of the laser pulse. The ions, however, retain the millikelvin temperatures of the neutral atoms. This type of non-equilibrium ultracold plasma evolves rapidly, and many fundamental questions about its behaviour remain unanswered. Experiments conducted so far have revealed surprising dynamics and recombination behaviour that are pushing the limits of our knowledge of plasma physics.

Non-neutral plasma

The strength and range of the electric force and the good conductivity of plasmas usually ensure that the density of positive and negative charges in any sizeable region are equal (“quasineutrality“). A plasma that has a significant excess of charge density or that is, in the extreme case, composed of only a single species, is called a non-neutral plasma. In such a plasma, electric fields play a dominant role. Examples are charged particle beams, an electron cloud in a Penning trap, and positron plasmas[26].

Dusty plasma and grain plasma

A dusty plasma is one containing tiny charged particles of dust (typically found in space) that also behaves like a plasma. A plasma containing larger particles is called a grain plasma.

Mathematical descriptions

To completely describe the state of a plasma, we would need to write down all the

particle locations and velocities, and describe the electromagnetic field in the plasma region.

However, it is generally not practical or necessary to keep track of all the particles in a plasma.

Therefore, plasma physicists commonly use less detailed descriptions known as models, of which

there are two main types:

Fluid model

Fluid models describe plasmas in terms of smoothed quantities like density and averaged velocity

around each position (see Plasma parameters).

One simple fluid model, magnetohydrodynamics, treats the plasma as a single fluid governed by a combination of Maxwell’s Equations and the Navier Stokes Equations.

A more general description is the two-fluid picture, where the ions and electrons are described

separately. Fluid models are often accurate when collisionality is sufficiently high to keep

the plasma velocity distribution close to a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

Because fluid models usually describe the plasma in terms of a single flow at a certain

temperature at each spatial location, they can neither capture velocity space structures like beams or double layers nor resolve wave-particle effects.

Kinetic model

Kinetic models describe the particle velocity distribution function at each point in the plasma,

and therefore do not need to

assume a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. A kinetic description is often necessary for

collisionless plasmas. There are two common approaches to kinetic description of a plasma. One

is based on representing the smoothed distribution function on a grid in velocity and position.

The other, known as the particle-in-cell (PIC) technique, includes kinetic information by following the trajectories of a large number of individual particles. Kinetic models are generally more computationally intensive than fluid models. The Vlasov equation may be used to describe how a system of particles evolves in an electromagnetic environment.

Fields of active research

Timothy E. Eastman noted that:

- “The importance of the plasma sciences was formally recognized by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) in 1988 when they established the Plasma Science Committee”.[28]

This is just a partial list of topics. A more complete and organized list can be found on the Web site for Plasma science and technology [29].

|

|

Popular culture

- Plasma is often the discharge of rayguns: see plasma rifle.

- The Metroid series often has a plasma-based weapon, except in Echoes, where it was replaced by a laser based weapon, which behaved like plasma.

- In the Halo Universe, Covenant technology is mainly plasma-based.

- In the science fiction universe of Warhammer 40K there are highly unstable plasma weapons.

Footnotes

- ↑ Shalom. Eliezer, The Fourth State of Matter: An Introduction to Plasma Science, Published 2001 CRC Press, 338 pages, ISBN 0750307404 (Page 2)

- ↑ Radu Balescu, “Aspects of Anomalous Transport in Plasmas”, Published 2005 CRC Press, 319 pages

ISBN 0750310308 (Page ix) - ↑ “Plasma — The First State of Matter“, Coalition for Plasma Science. (See also in PDF)

- ↑ Greg Morfill et al, Focus on Complex (Dusty) Plasmas (2003) New J. Phys. 5

- ↑ Crookes presented a lecture to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, in Sheffield, on Friday, 22nd August 1879 [1] [2]

- ↑ Announced in his evening lecture to the Royal Institution on Friday, 30th April 1897, and published in Philosophical Magazine, 44, 293 [3]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 I. Langmuir, “Oscillations in ionized gases,” Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S., vol. 14, p. 628, 1928

- ↑ G. L. Rogoff, Ed., IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science, vol. 19, p. 989, Dec. 1991. See extract at http://www.plasmacoalition.org/what.htm referring to L. Tonks, “The birth of ‘plasma’” Amer. J. Phys., vol. 35, pp. 857-858, 1967.

- ↑ D. A. Gurnett, A. Bhattacharjee, Introduction to Plasma Physics: With Space and Laboratory Applications (2005) (Page 2). Also K Scherer, H Fichtner, B Heber, “Space Weather: The Physics Behind a Slogan” (2005) (Page 138)

- ↑ Plasma fountain Source, press release: Solar Wind Squeezes Some of Earth’s Atmosphere into Space

- ↑ After Peratt, A. L., “Advances in Numerical Modeling of Astrophysical and Space Plasmas” (1966) Astrophysics and Space Science, v. 242, Issue 1/2, p. 93-163.

- ↑ See The Nonneutral Plasma Group at the University of California, San Diego

- ↑ See Flashes in the Sky: Earth’s Gamma-Ray Bursts Triggered by Lightning

- ↑ Richard Fitzpatrick, Introduction to Plasma Physics, Magnetized plasmas

- ↑ Dickel, J. R., “The Filaments in Supernova Remnants: Sheets, Strings, Ribbons, or?” (1990) Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, Vol. 22, p.832

- ↑ Grydeland, T., et al, “Interferometric observations of filamentary structures associated with plasma instability in the auroral ionosphere” (2003) Geophysical Research Letters, Volume 30, Issue 6, pp. 71-1

- ↑ Moss, Gregory D., et al, “Monte Carlo model for analysis of thermal runaway electrons in streamer tips in transient luminous events and streamer zones of lightning leaders” (2006) Journal of Geophysical Research, Volume 111, Issue A2, CiteID A02307

- ↑ Doherty, Lowell R., “Filamentary Structure in Solar Prominences.” (1965) Astrophysical Journal, vol. 141, p.251

- ↑ Hubble views the Crab Nebula M1: The Crab Nebula Filaments

- ↑ Zhang, Yan-An, et al, “A rope-shaped solar filament and a IIIb flare” (2002) Chinese Astronomy and Astrophysics, Volume 26, Issue 4, p. 442-450

- ↑ See A Star with two North Poles

- ↑ See [Artist’s Conception of the Heliospheric Current Sheet http://quake.stanford.edu/~wso/gifs/HCS.html]

- ↑ Hannes Alfvén, Cosmic Plasma (1981) See section VI.13.1. Cellular Structure of Space.

- ↑ Horanyi, M. et al, Dusty Plasma Effects in Saturn’s Rings (2004) American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2004, abstract #P52A-07. See also Blikoh, P. V. et al pokes in the Saturn’s Ring as Solutions in Dusty Plasma (1994) Dusty and Dirty Plasmas, Noise, and Chaos in Space and in the Laboratory. Edited by Hiroshi Kikuchi. ISBN 0-306-44839-4. Published by Plenum Press, New York, 1994, p.29

- ↑ See Saturn: Rings

- ↑ R. G. Greaves, M. D. Tinkle, and C. M. Surko, “Creation and uses of positron plasmas“, Physics of Plasmas — May 1994 — Volume 1, Issue 5, pp. 1439-1446

- ↑ See Evolution of the Solar System, 1976)

- ↑ Timothy E. Eastman, Plasmas: “Diversity, Pervasiveness and Potential“, Journal of Fusion Energy, ISSN: 0164-0313, Volume 17, Number 2 / June, 1998

- ↑ Web site for Plasma science and technology

See also

Template:Portal

Template:Wiktionary

Template:Commonscat

- Plasma parameters

- Magnetohydrodynamics

- Electric field screening

- List of plasma physicists

- Large Helical Device

- Important publications in plasma physics

- IEEE Nuclear and Plasma Sciences Society

- A plasma channel is a conductive channel of plasma.

External links

- Plasmas: the Fourth State of Matter

- Plasma Science and Technology

- Plasma on the Internet comprehensive list of plasma related links.

- Introduction to Plasma Physics: Graduate course given by Richard Fitzpatrick | M.I.T. Introduction by I.H.Hutchinson

- An overview of plasma links and applications

- NRL Plasma Formulary online (or an html version)

- Plasma Coalition page

- Plasma Material Interaction

- How to make a glowing ball of plasma in your microwave with a grape | More (Video)

- How to make plasma in your microwave with only one match (video)

- U.S. Dept of Agriculture research project “Decontamination of Fresh Produce with Cold Plasma”

- CNRS LAEPT “Electric Arc Thermal Plasmas